¤

In the opening scene of Peter Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon, a man who we are expected to believe is named “Moses Pray” parks his car on the side of a road in rural Kansas. In one shot, we can see nothing but Moses, his car, a copse in the distance, and a couple of gravestones in the foreground. The rest is simply flat, the horizon extending forever. The funeral service he’s crashing is not much busier: a preacher, a pair of women from nearby Gorham, and a nine-year-old girl, the daughter of the deceased. When Moses stoops down to swipe a bouquet of flowers from one of those unattended graves on his way to joining, it’s difficult to imagine the thievery going unnoticed.

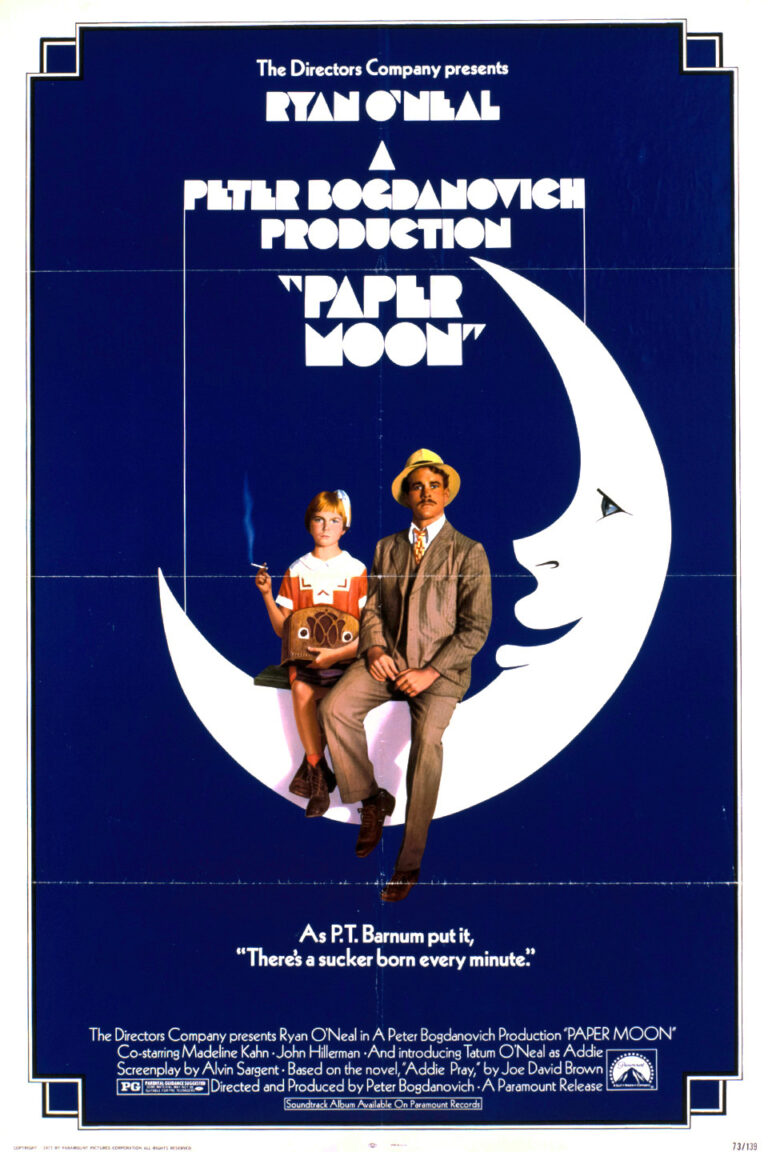

Paper Moon, which was released 50 years ago this spring, is shot in black and white and set in the Depression. The bouquet-swiping primes the audience to laugh at the scene, but the image is nearly classical: a group of people huddled against the elements, sticking to the letter of religious rites handed down across generations. Setting this against the Kansan expanse underlines the oddity of those rites being towed as cargo to America by European settlers. Decades later, this is where the modern evangelical movement would take hold, with its gaudily corporate megachurches and unwavering tonal kayfabe. But for now, it’s just this, three adults hoping a sincere reading of Psalm 26 — where a word is alternately translated, in various versions of the Bible, as “deceitful,” “evil,” and “vain” — will bring a little comfort to a child.

That girl, Addie, is stoic; when the adults pull her a cup of water from a nearby well, she dumps it on the ground where they can’t see. They’re distracted by the resemblance between Addie and Moses. “It seems you’ve got the child’s jaw,” one says, explaining that she has no kin this side of Missouri. Eventually, Moses is harangued (or: appears harangued) into driving her the 250ish miles to that Missouri aunt’s house. Supposedly burdened, Moses loads Addie in his car — and drives straight to the grain mill owned by the brother of the man who killed Addie’s mother in a drunk driving accident.

Moses uses Addie as a prop, introducing her to the man before telling her to wait outside while he extorts $200 (a little over four grand today) out of him. Most of this money, in turn, goes to a mechanic who fixes his car and toward a train ticket for Addie. There is a catch: Addie heard his conversation at the mill. She demands the $200 that is rightfully hers, and which Moses no longer has. With no other options, he cancels her train ticket — collecting a refund, of course — and brings her to work with him.

“Work” is traveling Bible sales, though that implies a more straightforward transaction than the ones Moses is interested in. Combing the obituaries sections of local newspapers for addresses of the bereaved, he shows up on doorsteps with Bibles the departed allegedly ordered in the final weeks of their lives: gaudily embossed editions, inscribed to a survivor — a woman, always — whose name he learned that morning over coffee and eggs. Moses will feign shock — he’ll take off his hat — he’ll offer, in good faith, to return the deposit put down by the dead. Naturally, no one takes him up on this. (“Of course I’m obliged,” one says when Moses reminds her she can cancel the purchase. “He ordered the deluxe!”) Mothers and wives are flattered, especially when their sons and husbands hadn’t been praying men.

Addie takes to the business immediately, peering into foyers to eyeball furniture and get a sense for which mourners she and her “father” — the act is a family business — can gouge. This also gives her the power to “remind” Moses that certain balances have been paid in full when she takes pity on the families who open their front doors. And still, the money flows. Addie and Moses whittle away at the $200 balance, staying in motels where Addie smokes cigarettes in bed as she listens to Jack Benny radio broadcasts before bed.

The cigarettes are funny, but they also make Addie appear as she wants to: unbothered, inscrutable, older than she is. And yet she knows when to back off of this gesture, behaving as innocently as is necessary to coax money out of marks. Moses, similarly, is convincing to everyone but the omniscient audience as a man of deep faith and zero financial ambitions. But he’s not as clever as she is, or as acutely aware of when to toggle between the two modes. Like all con artists — or maybe: like all con artists in the moralizing tales about them — he pushes too far, inviting legal and then extralegal danger when he steals a bootlegger’s whiskey and tries to sell it back to him. The pair only escape their initial arrest due to Addie’s ingenuity — she, after all, has been learning how to con since most children were practicing long division. The deception is as intrinsic to her as the psalms were to the crying women at her mother’s grave.

Running through Paper Moon is the open question of whether Moses is Addie’s father. While vulturing a girl who was orphaned by a man from a rich family is in line with his other cons, Moses did have a relationship with Addie’s mother. And the resemblance is striking, for good reason: after working with Ryan O’Neal on 1972’s What’s Up, Doc?, Bodganovich decided to cast him as the lead of his next project, and O’Neal’s daughter Tatum as Addie. Tatum is to this day the youngest person to ever win a competitive Oscar, taking home the Best Supporting Actress trophy when she was just 10 years old. But the tenderness O’Neal and Tatum came to show one another onscreen was, like Addie’s innocence and Moses’s piety, an illusion.

The two became so thoroughly estranged that, at his partner Farrah Fawcett’s 2009 funeral, O’Neal told Vanity Fair that he “had just put the casket in the hearse […] when “a beautiful blonde woman” approached him. He asked her if she had any liquor on her and a car nearby. “Daddy, it’s me,” the woman replied. “It’s Tatum!”

¤

Around 1980, a young man from Los Angeles named Robert Greene graduated from the University of Wisconsin–Madison with a degree in classical studies. He kicked around Europe for a bit, working odd jobs; he did a stint at Esquire in New York; he taught and translated and eventually moved home, with the notion that he might try screenplays. Then, when he was approaching 40, he wrote a book that would go on to become a massive bestseller and presage an era when bullshit would stop being an art and start becoming blunter, broader, and more indistinguishable from nearly everything surrounding it.

The 48 Laws of Power, published 25 years ago, draws its bromidey lessons from politicians, military leaders, and writers across history. The names are, on the whole, unsurprising: Henry Kissinger, Sun Tzu, Carl von Clausewitz. Some of the lessons (“Pose as a Friend, Work as a Spy”) carry with them the light sociopathy of all business-speak, but most — “Think as You Like but Behave Like Others”; “Be Royal in Your Own Fashion: Act Like a King to Be Treated Like One”; “Make Your Accomplishments Seem Effortless”; “Enter Action with Boldness” — are so vague and self-contradictory as to arrange themselves into a prism of nothingness. People joke about horoscopes being purposefully nonspecific so as to convince readers, ironically, of their specific wisdom; Greene’s book makes “Tuesday for Taurus” columns look positively surgical in their precision.

The obvious parallel is Machiavelli. But where The Prince has for centuries flummoxed scholars who try to diagram its sincerity versus its satiric — or at least derisive — quality, Greene shows no such imagination or playfulness. While he argues that “[p]ower is essentially amoral,” 48 Laws never turns a critical eye to the unintended consequences of its advice, and is therefore an essentially immoral document. It would be dangerous if it were even a little bit compelling.

Despite all of this, 48 Laws earned Greene the reputation of a guru on not only power, but also sex (2001’s The Art of Seduction, a book whose cover is, well, suggestive, and whose content is the clear blueprint for the proliferation of 2000s pickup-artist culture and media), combat (2006’s The 33 Strategies of War), and genius (2012’s Mastery). By 2018, he had dropped the pretense and declared himself the reigning expert on The Laws of Human Nature.

Over the course of the 21st century, this dead-eyed worship of a nebulous “success” has been so thoroughly metabolized into the culture that it’s impossible to escape. See the Instagram posts urging you to get out of bed and make money — or, alternately, to forgo money on the way to making money — backed by images of Kobe Bryant or Steve Jobs; see figures like Jordan Peterson, who turned advice like “clean your room” and “sit up straight” into a wildly lucrative cult of personality; see, even, the language of wellness culture that increasingly speaks of mental and physical health in terms that could easily head Excel columns. Bullshit is now big business, and therefore no longer bullshit; there are no little girls smoking in a motel room a mile away, plotting on your last 10 dollars.

We’ve become so starved for artful bullshit that we strain to see it where none exists. Think about all the essays you read claiming that Donald Trump was the perfect emblem of his era, one dominated by “grifters.” This is a total misreading: while Trump ran a predictably dodgy real estate training program and routinely stiffed contractors and construction companies working on properties he owned, there was no sleight of hand. Trump was first a symptom of, and then a driving force behind, an ideological shift toward the lionization of cutthroat business practices, even when they come at the expense of that ideology’s adherents. The cruelty and vacuousness of the era are not drawbacks but evidence of Trump et al.’s dedication to success. The Steinbeck quote about Americans seeing themselves as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires” is now somewhat beside the point — there is open cheering for figures whose wealth no one assumes they could ever achieve.

Even scams and plots that have been romanticized recently, like the story of Anna Sorokin, who posed as a wealthy heiress to drift through the New York art and society scenes in the mid-2010s, have captivated people primarily as anachronisms, recalling a time before online banking and the Patriot Act when one could conceivably turn their life into a private performance exhibit and stay a half-step ahead of the exes and creditors nipping at their expensive heels. At the end of Paper Moon, after Moses finally drops Addie off at her aunt’s house in Missouri, the young artist has a shock of realization, then runs down the highway after her pretend father: he still owes her $200.

¤

Paul Thompson is a senior editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books. He has written for Rolling Stone, GQ, New York, Pitchfork, and The Washington Post, among other publications.